Redefining sitcoms with The Good Place

Or: holy motherforking shirtballs.

Note: as you can probably guess, this essay contains major spoilers for the first season of The Good Place. I’d really recommend watching it before reading this…

How do you define a sitcom?

James Cary describes them as a ‘permanent act two’:

Your characters are trapped in a situation, usually a complex web of relationships as much as a location. In this precinct, they go round and round in circles, never learning, never changing and never significantly altering their situation.

That doesn’t mean they’re completely static; Monica and Chandler got married, Niles and Daphne got married, Pierce Hawthorne died of… dehydration.1 But the changes are slow, and the dynamic is more or less the same in episode 100 as it was in episode two. That’s why you could come home from school, tune into a random episode of Friends, and follow what’s happening instead of needing to hang out with real people.

That said, there are sitcoms that have played around with longer narratives.

The first such sitcom I remember watching was Arrested Development, which blew blue me away with it’s tightly-packed story of a wealthy family who lost everything (and the one son who had no choice but to keep them altogether). Arguably ahead of its time, it had callbacks, foreshadowing and major plot developments which I’m convinced were at least partially constructed around wordplay (“loose seal!”).

Then there was The Wrong Mans, which was intentionally written with a bigger story in mind, and was a delightful hoot despite the fact that it had James Corden in it:2

It was that time everyone started watching those TV box sets like 24… We thought, ‘I wonder why no-one’s tried to do that in a half-hour BBC comedy?’ We wanted to write a sitcom that still had those cliffhangers you get at the end of Breaking Bad and 24 which make you go: ‘I have to watch the next one right now!’

After that, I loved the criminally-underrated The Last Man on Earth, worth watching for the boldness of its pilot alone (featuring, as the name suggests, just one character) — but alas tragically cancelled before it could wrap everything up.

And then there was The Good Place.

If you’re not familiar with it: the premise of The Good Place is that the main character, Eleanor Shellstrop, has died, and ends up in a heaven-like afterlife known as the Good Place. However, she quickly realises she’s there by mistake — they’ve got the wrong Eleanor — and if she’s caught, she’s doomed to eternal damnation in the Bad Place:

So she hides the truth from Michael, the ‘architect’ of the Good Place, and tries to become a better person in the hope of legitimately earning her spot.

She gets some help from the people she meets, including an actual professor of moral philosophy called Chidi. But she’s faced with an unrelenting, perhaps even torturous series of obstacles — before finally making an epic realisation in the season one finale: they’ve been in the Bad Place all along. And Michael was behind the whole thing.

I’m not exaggerating when I say this blew my mind, and I genuinely believe it’s one of the most well-executed twists ever committed to screen.3

It completely opened my eyes to what a sitcom can be, and I now feel like it’s my life’s mission to master this particular form: a half-hour show with a twisty-turny narrative but the gag-rate of a traditional sitcom. As I wrote about before, I’ve been working on one such project for a while now — so here are three lessons from The Good Place I’ve tried to keep in the back of my mind while doing so…

1. Burn through your best stuff

A great piece of writing advice that I 100% know to be true but am approximately 20% disciplined at following is don’t save your best stuff for later.

So when you’re working on a pilot, the thing you’re saving for the end of the episode should probably happen at the end of act one. And when you’re working on the pitch that goes with it, the thing you’re saving for the season one finale (or even season two) should probably happen in like episode three.4

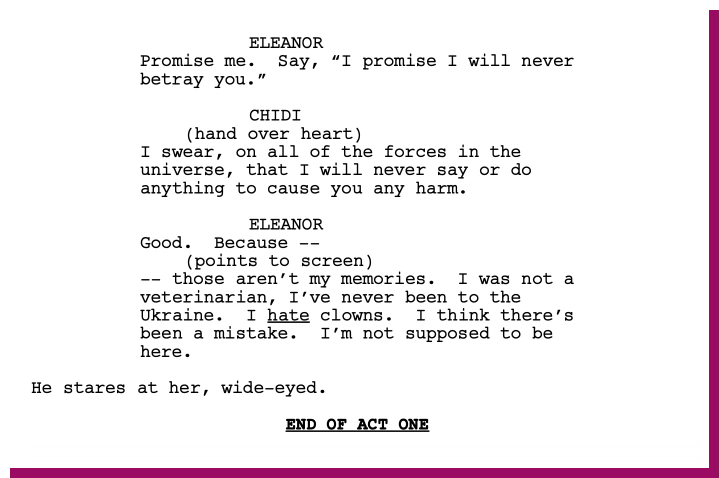

The first season of The Good Place is especially good at this. In the pilot, Eleanor tells Chidi that she’s there by mistake at the act one break — whereas a weaker version of the script might have saved it as a cliffhanger for the end of the episode.

And while it might’ve been tempting to keep playing with this premise forever — will the truth come out? — she ends up confessing in episode seven. As Michael Schur, the creator of The Good Place, explains in the excellent Script Apart podcast:

If you make a pilot with an enormous premise, then what happens is that the premise burns off after a while. It’s the same thing every time — she’s almost getting caught, she figures out a way to wriggle free — and you just start to get bored because who cares? Like I’ve seen this before. It’s like watching a movie ten times in a row. So I had this real serious feeling, even before I had the big twist at the end of the first season, that new stuff needed to be happening all the time.

As a result, the developments keep coming at a relentless place, with some major new revelation at the end of almost every episode. But they weren’t just random revelations; they really felt like they were building up to something. Which leads to point two:

2. Know where you’re going

The original version of this essay was about what makes a great twist. I’ll save those thoughts for another time (or will I??), but for now, I’ll define them as:

Something you didn’t see coming

Which reframes what you already know

In a way that makes sense

Twists that feel underwhelming tend to focus on point one, but it’s point two (at the time) and point three (when you’re thinking about it afterwards) that make them truly memorable. And the only way to get those right is to know where you’re going.

As I wrote above, I think The Good Place absolutely nailed this, and part of the reason was that Schur developed the idea for longer than usual:

At a point where I would have ordinarily gone to my bosses and pitched them the show, I thought: I can’t do this yet… This was heavily serialised, and it had all these twists and turns. It felt like Lost or something… And in fact, I talked to [one of the creators] Damon Lindelof about the show, and said: what pitfalls am I gonna fall into here? And the number one thing he said was: you have to know where you’re going. If you don’t know what the endpoint is, you’ll tread water and people will get annoyed, because that’s what happened to them on Lost.5

With this in mind, I’ve spent way more time figuring out my current project than I might’ve done for a ‘normal’ one. (I was going to write out exactly how long, but then had a small existential crisis about the relentless passing of time.)

Admittedly, this might turn out to be a tactical error, and I should’ve spent that time on several simpler projects instead. But… I don’t actually have a counterpoint to that. Something about pride in my work? I guess I’ll let you know.

And then there’s one last thing:

3. Don’t forget it’s a sitcom

And so we come back to my original question: how do you define a sitcom?

Because despite all of the twists, bold themes and sheer ambition, my favourite thing about The Good Place is that it still feels like a sitcom. In fact, as Joel Morris pointed out in his Comfort Blanket podcast, the architect Michael literally creates one:6

[Schur has] complete faith in the sitcom as a form. And what he does, and I only noticed it this time around, is that he builds a thing in which sitcom god Ted Danson [Michael] builds a sitcom where they live. Because every sitcom is throwing four disparate characters together and trapping them somewhere… This is Sartre’s ‘Hell is other people’. Well, that’s what a sitcom is.

In other words, it’s a love letter to sitcoms themselves:

I think it’s a sensationally confident show. And one of the reasons it that Michael Schur, who made it, had made lots of these and clearly loves the form… This is a sitcom about sitcom about the love of sitcom and a belief and a faith in the half-hour comedy or the 24-minute comedy to tell incredible stories of a standard that could be told by any other art form.

As I’ve written about previously, it does feel like sitcoms are in a bit of a bleak place at the moment. But while the main theme of The Good Place might be how to be a better person, it also reminds us how magical sitcoms can be; a place where you can ponder the deepest questions of human existence while a character describes their ‘bud hole’.

So how do I define a sitcom?

An art form that’s definitely worth fighting for.

(But also: “n. a situation comedy.”) 🚀

p.s. a friendly reminder that my scratch night for sketch comedy films, Sketchburn, is back on Monday, 31st March at the Etcetera Theatre in Camden! More details here…

I once would’ve described The Simpsons as the purest example of a sitcom, as the characters don’t even age. But it’s now been running for so long that it’s developed its own set of weird time-shifting phenomena — like in S33 E1 The Star of the Backstage, which describes Marge as going to high school in the late 90s?? This is upsetting for so many reasons.

I usually have a policy of not criticising other people or work here, and focusing on the things I like, but I think it’s okay to violate this principle for James Corden?

I rewatch the reveal every now and again, and it still gives me chills. It’s also fun to watch some of the cast hearing about it for the first time…

Not only is this better for the finished product, but as my friend Ish once pointed out: the current version of the thing is most likely the last version of the thing you’ll ever get to work on. There’s a < 0.001% chance that this script is going to get made — if that! — so I might as well get to the good stuff. This is basically the screenwriting equivalent of ‘live every day like it’s your last’, which is actually terrible life advice but works pretty well here.

An interesting trait I’ve noted about Schur is that he doesn’t hesitate to just ask people for things, advice or otherwise. I really recommend listening to his episode of The Tim Ferris Show, where he talks about e.g. emailing philosophers to ask them about moral philosophy, and convincing David Foster Wallace to hang out with the Harvard Lampoon.

I’m literally doing the final redraft of this and I only just clocked that the character of Michael has the same name as the show’s creator.